The following articles are all reproduced from an exibition held at St. Gregory’s Church in June 2007, where to this day the head of Simon is kept.

Simon as Bishop of London

It is possible that his father’s connections (Nigel Theobald) with Elizabeth de Burgh, Lady of Clare and Grand-daughter of Edward II, may have smoothed the path of Simon’s career. Influential connections were necessary but it also helped if your father was a wealthy merchant able to advance loans to the king to finance his wars with France.

However, the plain fact was that Simon had been good at his job, whether for the Church or as a diplomat. When the promotion came as Bishop of London in 1361, it had been thoroughly earned.

The substantial revenues of his bishopric enabled him to begin a new career as benefactor, builder, and patron of art. In Sudbury he was responsible for starting the work on the virtual total rebuilding of St. Gregory’s Church.

He drew up the constitution for the running of St. Leonards Hospital for Lepers in Melford Road. But he is chiefly remembered in this town for the founding of his College for the training of priests.

Apparently he was appalled to discover that many of the priests in his diocese and elsewhere were ignorant of the meaning of much of what they were reciting during the services. He was determined that the two churches in the parish where he was raised would be better served.

Simon as Diplomat

The English possession of the duchy of Aquitaine caused a tension in Anglo-French relations. Even more so with Edward III’s claim to the French throne and fear of a French alliance with Scotland.

In 1338 Edward invaded France in the first of a series of campaigns which were to become The Hundred Years War Anti French feeling was intensified by the fact that Pope Clement V (1305-14) had moved the Papacy to Avignon, in France. With the outbreak of war the efforts of the Papacy to promote peace, which served French acquisitive aims more than anything, aroused intense hostility in England.

In 1349 Simon took up a position in the service of the Papacy as an Auditor of Causes in the Papal Court at Avignon. Just prior to that he had been made a Canon at Hereford.

He was awarded the post of Chaplain to Pope Innocent (1352-62) then was sent to England as Nuncio (Papal Ambassador) to Edward. He was engaged in several diplomatic missions and gained a reputation for being ‘learned, eloquent and liberal’.

In 1353 he was made a Canon at Salisbury and he also held the Prebend of Henstridge at Wells, which was later passed, to his brother John and then to his younger brother Thomas.

Simon’s College

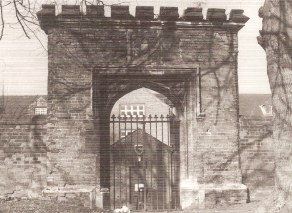

Update November 2009 – The remains of the arch have now been restored (see picture right) with the help of funds provided by this society.

The picture below is of the remains of Simon’ s College and it is dated 1818., from a drawing by T. Higham and engraved by Neale for a book illustration. It shows the building when it was being used as a workhouse. It was totally destroyed to make way for a new workhouse in 1836 designed by John Brown of Norwich, which is now called Walnuttree Hospital.

We cannot be sure when the idea for the College was first conceived. Neither do we know whether the idea was discussed with his father before his death. What we do know is that the substantial Theobald house and grounds were ideally situated abutting the St. Gregory’s churchyard to the west and that not much was needed to adapt it for their purpose.

Secondly the St. Peter’s Chapel of Ease was being rebuilt on a grand scale on a spectacular new site and when completed would be larger than the ‘Mother Church’.

At St. Gregory’s the North Aisle had been rebuilt at the expense of the Theobalds and the chapel containing their parent’s remains was joined to it. It made sense therefore to try to acquire the church and raise it to Collegiate Status.

The advowson of the church had been given to the Nuns at Eaton in Warwickshire by the Earl of Gloucester in the mid 12th century. It would be necessary to retrieve it from them.

Simon’s status as Bishop of London and the subsequent increase in his spending power had enabled him to invest in City of London property. He was an honest man and calculated that the value of the rents from four shops in the City would be more useful to the Nuns than the advowson of a church many miles away with all its responsibilities.

The Nuns agreed!!

It is interesting to remember that Simon’s Diocese of London reached right up to the Essex bank of the River Stour. The proposed site of the College and the church to which it would be attached was on the Suffolk bank and in the Diocese of Norwich. He was obliged therefore to seek permission from the Bishop of Norwich to proceed. An agreement was reached on Nov. 1st 1374 between the two for the foundation in connection with St. Gregory’s Church.

A second agreement dated August 9th 1375 involves Simon’s brother John as a third party, because Simon had been promoted and had become Archbishop of Canterbury.

The actual Royal Charter of Edward III for the foundation of Sudbury College is dated Feb. 21st 1375. The head of the College was The Warden (or Custos) and under him were five secular canons and three chaplains whose duty was to perform the Divine office daily in the two churches of St. Gregory and St. Peter.

These numbers were increased at a later date.

In 1382 Richard II granted his licence for Simon and John to give to the College further lands and tenements together with the Manors of Middleton Hall and Ballingdon which they had purchased from St. Alban’s Abbey.

Subsequently Kitchen Farm and the Manor and Church of Brundon would be included with their possessions.

The Chapel of Ease

St. Peter’s Chapel, founded in the 12th century by William FitzRobert, Earl of Gloucester, was first sited within the Great Ditch. Work began on the new Chapel c.1327 and when completed with extensions c.1425-40 it was larger than the ‘mother church’ of St. Gregory.

By the sixteenth century it had acquired the status of a Parish Church and part of the parish of St. Gregory was allocated to it.

Archbishop Simon of Sudbury

Simon was made Archbishop of Canterbury in the summer of 1375. A prematurely aged King Edward 111 was declining in health and depending a great deal on his son and heir Edward the Black Prince. However, sadly the Prince was also a slowly dying man having been infected by a fatal germ in Spain.

The Prince died on Trinity Sunday, 8 June 1376. His body lay in state at Westminster for nearly four months until his burial at Canterbury on Michaelmas Day at which Simon officiated.

In June the following year the King died and four weeks later, on 16 July 1377 the Black Prince’s son, Edward’s grandson, was crowned Richard 11 at Westminster Abbey by Simon. The Coronation marked the highpoint of his career as a churchman.

Richard was only nine years old and usually with a minor a Regency would be set up until he reached his majority. In the light of later events it was a tragedy that this did not happen in Richard’s case.

The only possible candidate for Regent was Richard’s uncle John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, probably the greatest noble in late medieval England. He was deeply unpopular, so much so that his candidature for Regent was ruled out.

Simon’s Building Work at Canterbury

It is doubtful whether Simon ever returned to Sudbury as Archbishop although of course he maintained contact with his brother John, now Warden or Custos of the College. He became heavily involved with building work at Canterbury, determined to make the city and Cathedral worthy of their status.

The old Norman nave of the Cathedral, hurriedly built just after The Conquest, was in a state of bad repair and unsafe and had been so for years. The decision to demolish it and rebuild from scratch came at the instigation of Simon though approval had to be sought from Christchurch Priory.

No doubt the fact that he was prepared to subsidise the costs by some 3,000 marks, equivalent to one and a half million pounds in our money today, helped.

He was responsible for the strengthening of the city walls and the rebuilding of the great Westgate. The King’s master mason, Henry Yevely, provided the designs for both nave and fortifications. He was no stranger to Simon having worked at St. Paul’s when he was Bishop of London.

Canterbury Nave is recognised as one of the greatest works of Perpendicular architecture in the country. Simon never lived to see it through, credit for that goes to Prior Thomas Chillenden who completed what Simon had begun.

St. Leonard’s Hospital (Colney’s Hospital)

John Colney, a prosperous merchant of Sudbury, had the misfortune to succumb to Leprosy. In 1372 he asked Simon to draw up certain ordinances for the control and governing of a hospital he was building outside the town in Melford Road.

The Hospital was in the form of three self-contained units one of which Colney himself would occupy as Warden or Governor. Two other lepers would each have a unit. After Colney’s death the vacancy would be filled and one would be chosen as Governor to whom the others would obey.

If a leper died, or was expelled, a replacement was to be found within six months, failing which the spiritual father of St. Gregory’s would nominate a third.

The annual income was divided into five portions, two to the Governor, two to the Brethren and one for maintenance. This fifth portion to be kept with the writings of the House, in a common chest in a safe place in some church in Sudbury.

If the statutes should not be kept after the Founder’s death the revenues were to be divided between the church of St. Gregory and the chapel of St. Anne, annexed to the same, in equal portions for the souls of Colney the Founder, and of Nigel and Sarah Theobald and all the faithful departed.

The Hospital was rebuilt as three almshouses in 1619-20 and continued to work well under Simon’s statutes until the last Master died in 1813.

In 1867 the net income was given towards St. Leonard’s Cottage Hospital in Newton Road via the Charity Commissioners. The almshouses were demolished in 1858 and replaced by a pair of double tenements which still stand today on the Melford Road near Colney’s Close.

The Peasant’s Revolt 13-15th June 1381

It was inevitable that it would happen it was just surprising that it hadn’t happened sooner. The causes were many and they started in the aftermath of The Black Death of 1348-9 that wiped out a third of the population that meant a crucial shortage of labour. The surviving labour forces were able to exploit the situation as for the first time competitive wages were offered.

In 1351 the government brought in The Statute of Labourers with a ruling that rents and wages should be fixed in an attempt to curb the situation. Successive governments did the same but with little success. The labourers resented these attempts to peg their wages. They had no intention of giving up their new found bargaining power in many cases, freedom.

Then there were the long drawn out wars with France and the continuous payment of taxes to keep them going. There was a growing animosity towards the Flemings, skilled craftsmen invited in by Edward III to show the English how to make good woollen cloth. They kept to themselves and dressed differently and they sent their money back to Flanders; or so it was said.

There was no single cause for the rebellion but a feeling by the population of being wronged on a number of scores. The nation had lost confidence in its government, its clergy, and itself. Each individual felt they knew who was responsible for their grievance and when the opportunity arose would seek satisfaction.

Marking the Anniversary in 2014

As the anniversary is upon us I just wondered if the following could be added to the website entry upon the town’s part in the Great Rising. It’s from RB Dobson’s The Peasants’ revolt of 1381, concerning the time when the rising began to collapse.

“The rebels who had been scattered, reassembled once more and went to Colchester where they began to incite the townsmen by means of urgent entreaties, threats and arguments to yet new disturbances and madness. But after failing to do this, they moved on to Sudbury. For they knew that Lords Fitzwalter and John Harlestone were following their route with an armed force. Suddenly, when the rebels were making their usual proclaimations on behalf of the commons, this force rushed upon them unexpectedly, killing as many as they wished. The remainder were allowed to live or sent to prison”.

I’ve also been ‘digging’ around the detail of the headless bodies found near the croft. The number 30 mooted is exactly the same figure of skeletons unearthed during the diggings on the site of the Holy Sepulchre church. Are these one and the same I wonder? If so it’s disputable whether they were victims of the retribution or just the usual remains to be found near any Medieval chapel.

This Thursday (12th June) a few of us are setting out from Liston Church on a walk past Lyons old Manor and onto Cavendish. Any Sudbury History Society are welcome to join us to mark the occasion, with a quick refreshment planned at the George before the walk back. We shall be at the crossroads in the village at 6pm.

Darren Clarke (Society member)

Simon the Chancellor

The biggest mistake in his career was when he accepted the post of Chancellor, even though a few years earlier it had been declared by Parliament that ” . . .. none but laymen henceforth be made Chancellor, Treasurer, or other great officer of the realm…”

Parliament assembled at Northampton in November 1380 to hear from him the dreadful financial situation the government was in.

The French expeditions had emptied the Treasury. There were three months wages due at the garrisons of Brest, Cherbourg and Calais. The king’s jewels were in pawn to the City of London as a surety for a loan of £5,000. The king needed the sum of £160,000 if they were to continue the war with France. There were troubles in Flanders that meant that exports of wool were down.

It was decided that there was no withdrawing from the war and so it was up to them to raise the money. They were given three options, a sales tax on all mercantile transactions, a wealth tax on property, or a poll tax amounting to one shilling and three groats per head on all persons over the age of fifteen.

They settled on a poll tax to raise £100,000 if the Church raised the rest. There was one proviso, the richest would pay up to six groats per man and wife so that the tax would fall less heavily on the others. A groat was the equivalent of four pence.

Parliament may have been in agreement but the Nation was not. The Peasants couldn’t and therefore wouldn’t pay. They rebelled and the revolt reached its climax with the dreadful events of 13-15th June when an estimated 100,000 peasants and supporters entered London.

On Friday 14th June the boy King Richard rode out from the Tower for a pre-arranged meeting with the mob at Mile End, he was showing amazing courage. After his departure nobody raised the drawbridge.

When the meeting with the rebels was over Richard returned to Baynards Castle near Blackfriars. Wat Tyler, the leader of the rebels went to the Tower with 400 men and met with no resistance. They found Simon and Hales, the Treasurer, at prayer in, St. John’s Chapel in the White Tower. They were dragged out of the building and taken to Tower Green where they were clumsily decapitated.

Their heads were fixed on to poles and paraded to Westminster and back to London Bridge where they were fixed above the gatehouse, the traditional place to display the heads of traitors.

The Suffolk Revolt

On the 12th June a detachment of Essex men led by a priest, John Wrawe, came over Ballingdon Bridge and were met by the Vicar of All Saints, Geofftey Parftey and a group of Sudbury men. They made their way to Liston Hall, about three miles north of Sudbury, which belonged to Richard Lyons a wealthy merchant and notorious moneylender and destroyed it.

They then moved on to Cavendish in search of Chief Justice Cavendish who was responsible for enforcing the Statute of Labourers in East Anglia. He had fled after storing his valuables in the church tower. The rebels demanded entry into the tower and carried of his goods.

They then went on to Melford where they stopped for refreshment and then made their way to St. Edmundsburywhere the Prior, John Cambridge, had been murdered by his own serfs. Eventually they tracked Cavendish down at Lakenheath where they beheaded him and carried his head back to St. Edmundsbury for display.

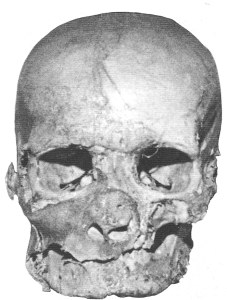

It was the Bishop of Norwich who restored order in East Anglia. None of the promises made by the King werehonoured and the leaders of the rebellion were executed. Wat Tyler’s head replaced Simon’s on London Bridge. Simon’s body was taken to Canterbury where his tomb is close to the Black Prince’s. His head was rescued and brought back to his beloved St. Gregory’s College, where it still is today.